HTTP Web Services

In this blog post I describe the process to create a simple Inventory app, following some best practices and guidelines of writing web services in GO.

Building a web service in Go is quite simple, in fact Go has a fast and powerful built in HTTP server. It takes just a couple of lines of code to get a basic HTTP server started. ListenAndServe starts an HTTP server with a given address and handler. The handler is usually nil, which means it use DefaultServeMux. Handle and HandleFunc add handlers to DefaultServeMux:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"net/http"

)

func main() {

http.HandleFunc("/", func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

fmt.Fprintf(w, "Hello World")

})

http.ListenAndServe(":8000", nil)

}

That’s cool, but it’s definitely far from being a full featured software App. There are more things to consider while designing even a simple REST API. In my previous blog posts I used a couple of web frameworks which kindly guided me in the process of defining and creating the services. Usually the frameworks are making our life easier as they bundle a lot of functionalities required by the project.

I still recommend looking to GoBuffallo if you are doing a big web based project and to consider GO-KIT for microservices. You can’t rely only to standard library when you are building a large scale service, it is possible but you’ll get a lot of challenges along the way and it may be less productive.

However, sometimes you want to build something fast which serves a targeted need, therefore using a framework it brings some unnecessary complexity. Below I’m creating a small REST API which it will serve me as boilerplate code for future projects.

Searching on the web for best practices to build and structure a REST API I found a number of resources. The ones that took my attention and I highly recommend to everyone to watch and read are the following:

- Mat Ryer’s talk on “How I write Go HTTP services after Eight Years"

- Kat Zien’s talk on “How Do You Structure Your Go Apps”

- Florin Patan’s talk on “Production Ready Go Service in 30 Minutes”

If you are looking for more in depth explanation on how to build & structure your application, check out the links below, which should give you a lot of insights on what is considered being the best practice:

- Ben Johnson’s article on “Standard Package Layout”

- Peter Bourgon’s article on “A theory of modern Go”

- Dave Cheney’s article on “Practical Go: Real world advice for writing maintainable Go programs”

- Ardan Labs “Service Training” which takes you step by step through the process of building a rest service from scratch

This is a small list, I’m sure that there are more great articles out there but this is good for start.

I’m not pretending that below I’m following all the recommended practices , in fact I know for sure that there is room for improvement. My intention here is to test them out and see what works for me. In the first part I’m following some ideas from Mark’s talk and in the second part I modify the script following Kat’s talk/example hexagonal design.

Flat Design , inspired by Mat’s talk:

I’m using flat design for simplicity, but can be migrated to a layered design pretty simple. Keep the main function as small as possible and defer functionality to other functions.

func main() {

if err := run(); err != nil {

fmt.Fprintf(os.Stderr, "%s\n", err)

os.Exit(1)

}

}

Create an api struct, a type that represents the component which include all the dependencies. This may eliminate the need to use a global state variable, which in the end improves maintainability and testability of the App. Use a constructor to create the api struct.

type api struct {

mutex sync.Mutex

db Memory

router *http.ServeMux

}

func newAPI() *api {

a := &api{

router: http.NewServeMux(),

mutex: sync.Mutex{},

}

a.routes()

return a

}

Implement ServeHTTP to turn your api into an http.Handler, which will be used whithin the http.Server struct.

func (a *api) ServeHTTP(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

a.router.ServeHTTP(w, r)

}

The main package simply wires up the pieces, choose which dependencies to inject into which objects. Use flag package to read the command line option for server listen address. Call the constructor to set the values of the api struct. Database dependency is not set up by the api constructor, I’m using the api struct for that.

I have implemented below gracefull shutdown, which allow the server to clean up some resources and to finish any user open request before it actually shuts down. For this I created 2 buffered channels, one which listen for errors coming from server and the other listen for an interrupt or terminate signal from the OS. The run function remains in blocking until a value from either channel is received and terminate the program.

func run() error {

flag.StringVar(&listenAddr, "listen-addr", ":5000", "server listen address")

flag.Parse()

API := newAPI()

API.db = Memory{}

API.PopulateItems()

fmt.Printf("there are %d of items in database\n", len(API.db.Items))

server := http.Server{

Addr: listenAddr,

Handler: API,

ReadTimeout: 5 * time.Second,

WriteTimeout: 10 * time.Second,

IdleTimeout: 15 * time.Second,

}

//channel to listen for errors coming from the listener.

serverErrors := make(chan error, 1)

go func() {

log.Printf("main : API listening on %s", listenAddr)

serverErrors <- server.ListenAndServe()

}()

//channel to listen for an interrupt or terminate signal from the OS.

shutdown := make(chan os.Signal, 1)

signal.Notify(shutdown, os.Interrupt, syscall.SIGTERM)

//blocking run and waiting for shutdown.

select {

case err := <-serverErrors:

return fmt.Errorf("error: starting server: %s", err)

case <-shutdown:

log.Println("main : Start shutdown")

//give outstanding requests a deadline for completion.

const timeout = 5 * time.Second

ctx, cancel := context.WithTimeout(context.Background(), timeout)

defer cancel()

// asking listener to shutdown

err := server.Shutdown(ctx)

if err != nil {

log.Printf("main : Graceful shutdown did not complete in %v : %v", timeout, err)

err = server.Close()

}

if err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("main : could not stop server gracefully : %v", err)

}

}

return nil

}

The HandlerFunc type is an adapter to allow the use of ordinary functions as HTTP handlers. If f is a function with the appropriate signature, HandlerFunc(f) is a Handler that calls f.

type HandlerFunc func(ResponseWriter, *Request)

Create routes.go file which maps out all the services. I think it’s a good idea instead of scattering them all around the application, as you can find all the endpoints in one place.

func (a *api) routes() {

a.router.HandleFunc("/", a.logger(a.handleLists()))

a.router.HandleFunc("/add", a.logger(a.handleAdd()))

a.router.HandleFunc("/open", a.logger(a.handleOpen()))

a.router.HandleFunc("/del", a.logger(a.handleDelete()))

}

Handlers are methods on the api, which gives them access to dependencies. In a similar manner I created the other handlers: handleAdd, handleOpen, handleDelete. I’m using HandlerFunc over handler. If you want to create a handler, with the HandlerFunc you do not have to create a type in order to do it since this gives you the option to use an annonymous function and cast it to the HTTP handler function.

func (a *api) handleLists() http.HandlerFunc {

return func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

data, err := a.listsGoods()

if err != nil {

a.respond(w, r, data, http.StatusNotFound)

}

a.respond(w, r, data, http.StatusOK)

}

}

Middlewares are normal go functions which takes in a handler as an argument and returns a new handler that can do different things. It can do things before calling the original handler or after calling the original handler.

func (a *api) logger(h http.HandlerFunc) http.HandlerFunc {

return func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

startTime := time.Now()

defer func() {

log.Printf("The client %s requested %v \n", r.RemoteAddr, r.URL)

log.Printf("It took %s to serve the request \n", time.Now().Sub(startTime))

}()

h(w, r)

}

}

Don’t have to repeat yourself every time you respond to user, instead you can use some helper functions.

func (a *api) respond(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request, data interface{}, status int) {

w.Header().Set("Content-Type", "application/json; charset=utf-8")

w.WriteHeader(status)

if data != nil {

err := json.NewEncoder(w).Encode(data)

if err != nil {

http.Error(w, "Could not encode in json", status)

}

}

}

func (a *api) decode(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request, v interface{}) error {

return json.NewDecoder(r.Body).Decode(v)

}

I’m using the api struct also when I’m doing storage CRUD operations:

func (a *api) addGood(items ...Item) (string, error) {

a.mutex.Lock()

defer a.mutex.Unlock()

for _, item := range items {

for _, i := range a.db.Items {

if item.ID == i.ID {

return "item already exists", nil

}

}

addtime := time.Now().Format(layoutRO)

addtime1, err := time.Parse(layoutRO, addtime)

if err != nil {

log.Printf("Can't parse the date, %v", err)

return "", fmt.Errorf("can't parse the date: %v", err)

}

if len(a.db.Items) == 0 {

item.ID = len(a.db.Items) + 1

} else {

lastItem := a.db.Items[len(a.db.Items)-1]

item.ID = lastItem.ID + 1

}

item.Created = timestamp{addtime1}

a.db.Items = append(a.db.Items, item)

}

return "Items has been added to database", nil

}

To test the handlers I created a mockedDatase, which is a simple slice of Items and within the test functions I setup the dependencies by using the same newAPI() constructor. If you are looking for a good resource to learn about testing in go I strongly recommend to watch Francesc Campoy’s video How to unit test HTTP servers.

var mockDatabase = []Item{

{

ID: 1,

Created: timestamp{time.Date(2019, 9, 05, 00, 00, 00, 00, time.UTC)},

Good: Good{

Name: "CannedOnion",

Manufactured: timestamp{time.Date(2019, 7, 02, 00, 00, 00, 00, time.UTC)},

ExpDate: timestamp{time.Date(2019, 10, 04, 00, 00, 00, 00, time.UTC)},

ExpOpen: 20,

},

IsOpen: true,

Opened: timestamp{time.Date(2019, 9, 03, 00, 00, 00, 00, time.UTC)},

},

}

func TestHandleAdd(t *testing.T) {

newItem := []byte(`[{

"id":2,

"name":"BottleMilk",

"manufactured":"03-08-2019",

"expdate":"02-11-2019",

"expopen":10,

"isopen":false

}]`)

srv := newAPI()

srv.db = Memory{mockDatabase}

req, err := http.NewRequest("POST", "/add", bytes.NewBuffer(newItem))

req.Header.Set("Content-Type", "application/json")

if err != nil {

t.Fatalf("could not create request: %v", err)

}

rec := httptest.NewRecorder()

srv.ServeHTTP(rec, req)

res := rec.Result()

defer res.Body.Close()

if res.StatusCode != http.StatusOK {

t.Errorf("expected status OK; got %v", res.Status)

}

if len(srv.db.Items) != 2 {

t.Fatalf("the item has not be inserted in database")

}

if srv.db.Items[1].Name != "BottleMilk" {

t.Fatalf("The item name expected to be BottleMilk but we got %s ", srv.db.Items[1].Name)

}

}

And the test results:

$ go test -v

=== RUN TestHandleLists

2019/09/16 15:25:01 The client requested /

2019/09/16 15:25:01 It took 125.258µs to serve the request

--- PASS: TestHandleLists (0.00s)

=== RUN TestHandleAdd

2019/09/16 15:25:01 The client requested /add

2019/09/16 15:25:01 It took 38.731µs to serve the request

--- PASS: TestHandleAdd (0.00s)

=== RUN TestHandleOpen

2019/09/16 15:25:01 The client requested /open?id=1&open=false

2019/09/16 15:25:01 It took 25.891µs to serve the request

--- PASS: TestHandleOpen (0.00s)

=== RUN TestHandleDelete

2019/09/16 15:25:01 The client requested /del?id=1

2019/09/16 15:25:01 It took 12.851µs to serve the request

--- PASS: TestHandleDelete (0.00s)

PASS

ok github.com/danrusei/http_web_services/api_flat_arch 0.003s

You can find the Full script implementation on GITHUB.

Hexagonal Architecture, inspired by Kat’s talk:

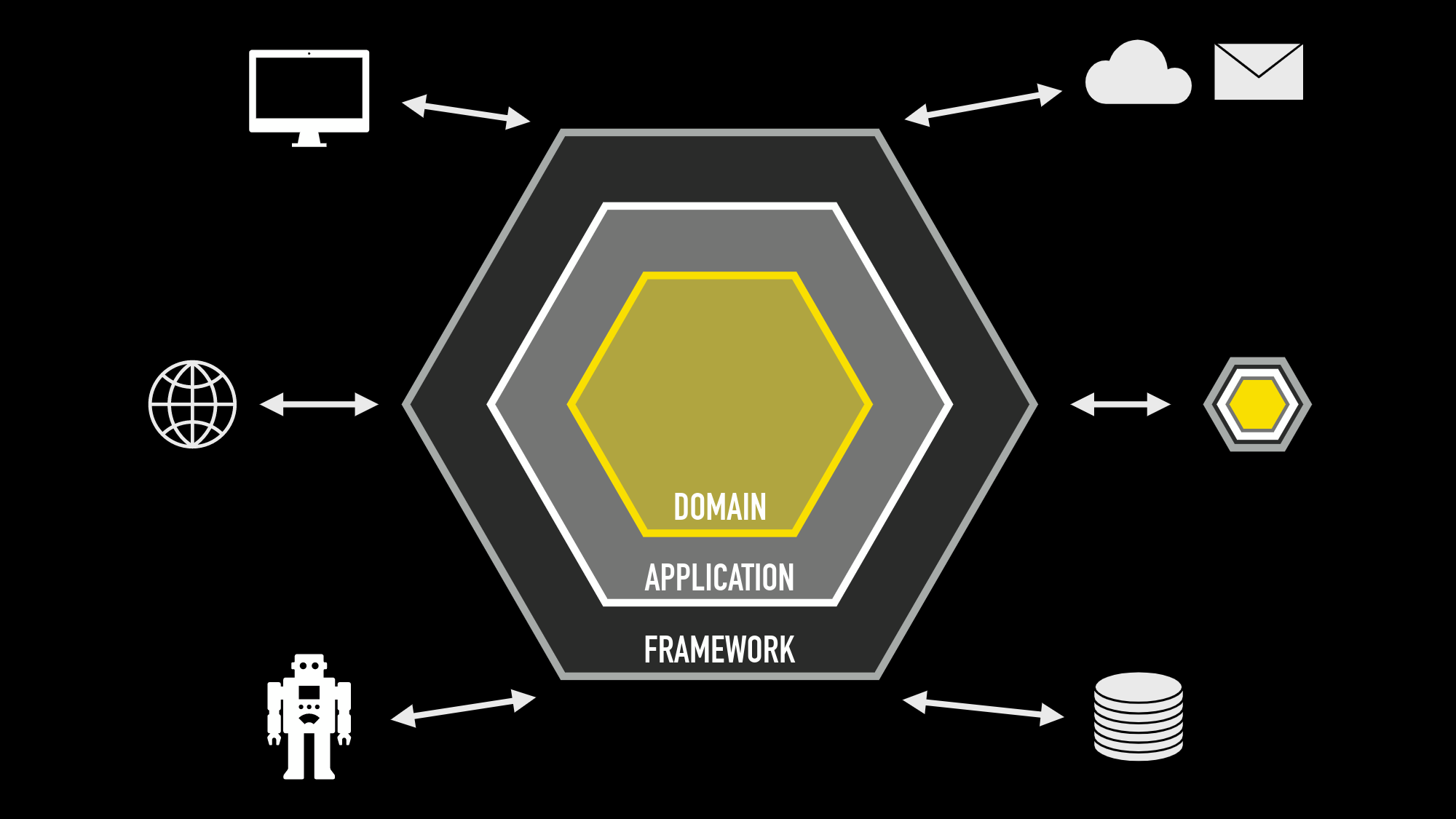

As the name implies, Hexagonal Architecture is represented by a hexagon. The figure below displays the entirety of the hexagon, with each of the sides representing a way that our system can communicate with other systems. For example, our system could communicate using an http, soap, rest, Sql, or a binary protocol and even with other hexagonal systems. Some of the advantages of the architecture is Maintainability and Flexibility as it allows you to easly modify and extend the program.

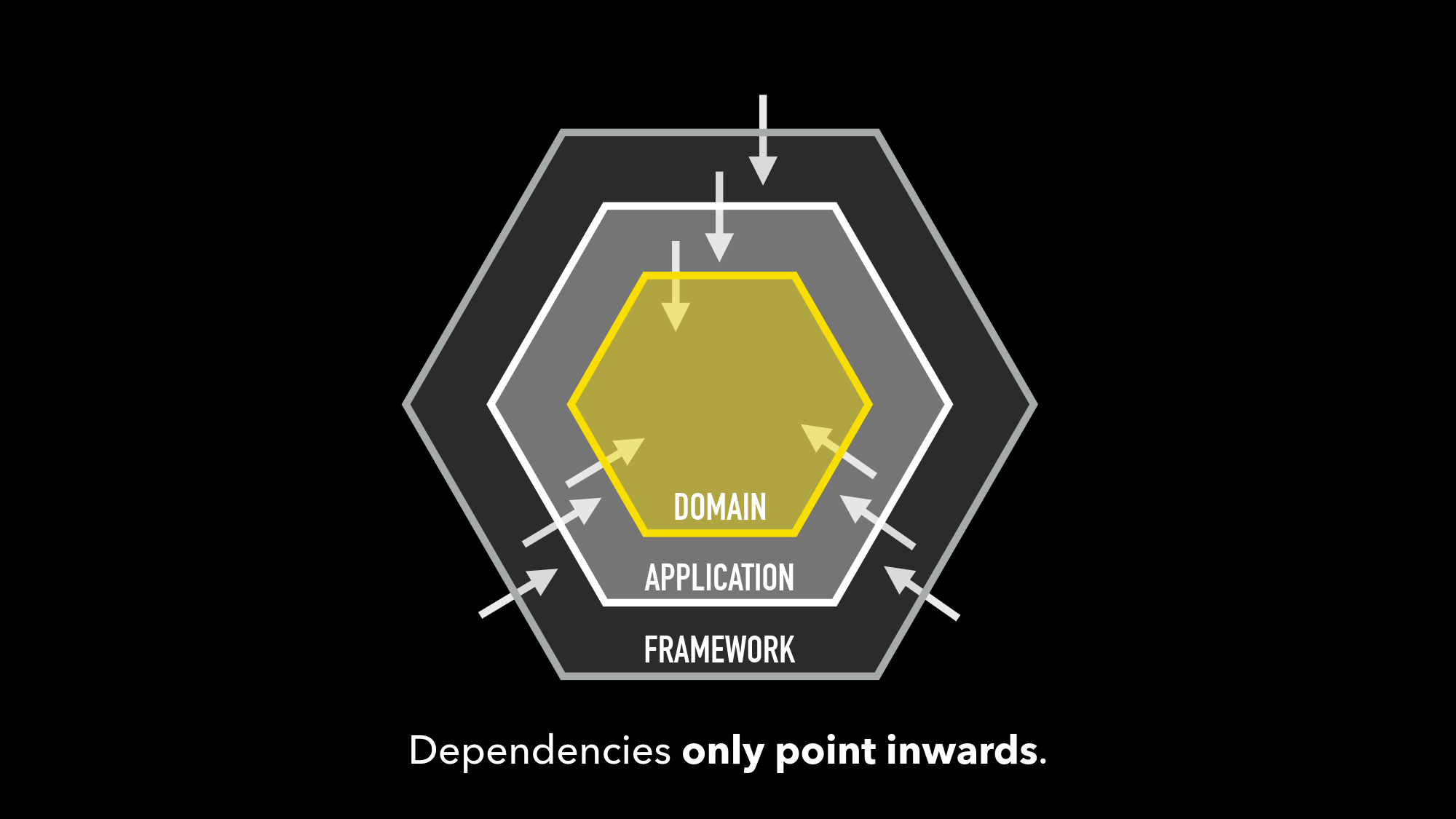

The dependencies should point only inwards, therefore the inner layers should not care about the outer layers, which implies a heavy usage of interfaces. The outer layers should satisfy the interfaces defined by inner layers.

The code is structured as follows: the top directories are cmd folder for the binaries and pkg folder for the rest of packages. Within the pkg folder there are adding, listing, opening, removing packages which are part of the core business domain. Below is the code for adding package, in similar manner other packages for CRUD operations are created. The NewService constructor set up the service struct adding the selected database and the service struct implements the Service interface.

package adding

import (

"errors"

"log"

)

// Service provides item adding operations.

type Service interface {

AddItem(...Item)

}

// Repository provides access to item repository.

type Repository interface {

AddItem(Item) error

}

type service struct {

r Repository

}

// NewService creates an adding service with the necessary dependencies

func NewService(r Repository) Service {

return &service{r}

}

// AddItem adds the given item(s) to the database

func (s *service) AddItem(items ...Item) {

for _, item := range items {

if err := s.r.AddItem(item); err != nil {

log.Printf("could not add the item: %v", err)

}

}

}

The memory package saves the data in a slice of Items. It satisfy the Repository interface from the adding package. Similarly the code is extended to the other CRUD operations. You can use whatever database you want if it satisfy the Repository interface.

package memory

//Storage storage keeps data in memory

type Storage struct {

items []Item

}

// AddItem add the item to repository

func (m *Storage) AddItem(it adding.Item) error {

for _, item := range m.items {

if it.ID == item.ID {

return fmt.Errorf("item %d already exists in database", it.ID)

}

}

if len(m.items) == 0 {

it.ID = len(m.items) + 1

} else {

lastItem := m.items[len(m.items)-1]

it.ID = lastItem.ID + 1

}

addtime := time.Now()

it.Created = addtime

newItem := Item{

ID: it.ID,

Created: it.Created,

Good: Good{

Name: it.Name,

Manufactured: it.Manufactured,

ExpDate: it.ExpDate,

ExpOpen: it.ExpOpen},

IsOpen: it.IsOpen,

Opened: it.Opened,

IsValid: it.IsValid,

}

m.items = append(m.items, newItem)

return nil

}

The communication layer do not care about the actual implementation, its solely role is to facilitate communication with outside world, in this case I use a REST API. It receive the Service interfaces through the constructor and it adds as arguments to handlers creation, so the functions can be called within the handlers.

package rest

//Handlers holds the dependencies

type Handlers struct {

lister listing.Service

adder adding.Service

opener opening.Service

remover removing.Service

}

//NewHandlers is the constructor for Handlers struct

func NewHandlers(l listing.Service, a adding.Service, o opening.Service, r removing.Service) *Handlers {

return &Handlers{

lister: l,

adder: a,

opener: o,

remover: r,

}

}

//SetupRoutes define the mux routes

func (h *Handlers) SetupRoutes(mux *http.ServeMux) {

mux.HandleFunc("/", h.logger(h.handleList(h.lister)))

mux.HandleFunc("/add", h.logger(h.handleAdd(h.adder)))

mux.HandleFunc("/state", h.logger(h.handleOpen(h.opener)))

mux.HandleFunc("/remove", h.logger(h.handleRemove(h.remover)))

}

//GetServer returns an http.Server

func (h *Handlers) GetServer(listenAddr string) *http.Server {

mux := http.NewServeMux()

h.SetupRoutes(mux)

server := http.Server{

Addr: listenAddr,

Handler: mux,

ReadTimeout: 5 * time.Second,

WriteTimeout: 10 * time.Second,

IdleTimeout: 15 * time.Second,

}

return &server

}

func (h *Handlers) handleAdd(s adding.Service) http.HandlerFunc {

return func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

var newItem []adding.Item

err := json.NewDecoder(r.Body).Decode(&newItem)

if err != nil {

http.Error(w, err.Error(), http.StatusBadRequest)

return

}

s.AddItem(newItem...)

w.Header().Set("Content-Type", "application/json")

json.NewEncoder(w).Encode("New item has been added.")

}

}

Last thing is to wire up all together within main function. I’m using dependency injection to build up the service. Dependency injection is a style of writing code such that the dependencies of a particular object (or, in go, a struct) are provided at the time the object is initialized.

package main

var (

listenAddr string

storageType string

)

func main() {

if err := run(); err != nil {

fmt.Fprintf(os.Stderr, "%s\n", err)

os.Exit(1)

}

}

func run() error {

flag.StringVar(&listenAddr, "listen-addr", ":5000", "server listen address")

flag.Parse()

store := new(memory.Storage)

var lister listing.Service

var adder adding.Service

var opener opening.Service

var remover removing.Service

lister = listing.NewService(store)

adder = adding.NewService(store)

opener = opening.NewService(store)

remover = removing.NewService(store)

//seed the database

adder.AddSampleItem(seed.PopulateItems())

// set up the HTTP server

h := rest.NewHandlers(lister, adder, opener, remover)

server := h.GetServer(listenAddr)

//channel to listen for errors coming from the listener.

serverErrors := make(chan error, 1)

go func() {

log.Printf("main : API listening on %s", listenAddr)

serverErrors <- server.ListenAndServe()

}()

...... continue with gracefull shutdown.

You can find the Full script implementation on GITHUB.

Conclusion

This script could serve me as boilerplate code for future small HTTP projects. Depending on the type of project I might choose one architecture over the other. I’m sure that the code and the samples will evolve in time to capture other best practices.

Let me conclude with:

Mat Ryer’s advices on factors to consider when writing HTTP services:

- Maintainability, the cost of maintaining can be bigger than the initial cost of creating the tool

- Glaceability, how quickly can you understand the code when you read through it

- Code should be boring, in the sense that everything about the codebase is obvious

- Self Similar code, write code that is similar to other code in the codebase

and Kat Zien’s conclusions:

- Two top-level directories, cmd for binaries and pkg for packages

- Group by context, no generic functionality

- Dependencies: own packages

- Mocks: shared subpackages

- All other project files (fixtures, resources, docs, Docker…): root dir of your project

- Main package initialises and ties everything together

- Avoid global scope and init()